We now enter the upward phase of a new Kondratieff cycle that would last from 1896 to 1920. The crisis of 1900 represents only a minor turning point in the American expansion of 1896–1907, while it marks a major turning point in Germany, Russia, and, to a lesser extent, France and Great Britain.

American prosperity extended from 1896 to 1907 and was interrupted by two minor recessions in 1899–1900 and 1902–1904. For the United States, this period may be considered a single Juglar cycle of 12 years, whereas in Europe two cycles can be observed. Investment flowed toward electric power, the telephone, metropolitan railways, and shipbuilding. The movement toward concentration and cartelization of firms continued in both the United States and Germany. Gold production increased following the discovery of the South African mines. Between 1895 and 1913, the world’s monetary gold stock grew by 3.7% per year. The recovery in Europe began around 1905, and all branches of economic activity benefited from the expansion, although railways no longer played a driving role. In the United States, electricity had taken first place, though railway development remained significant and continued to attract European capital. It is also worth noting that electric traction began to be used in tramways. The chemical industry also contributed to growth, and the first automobiles appeared.

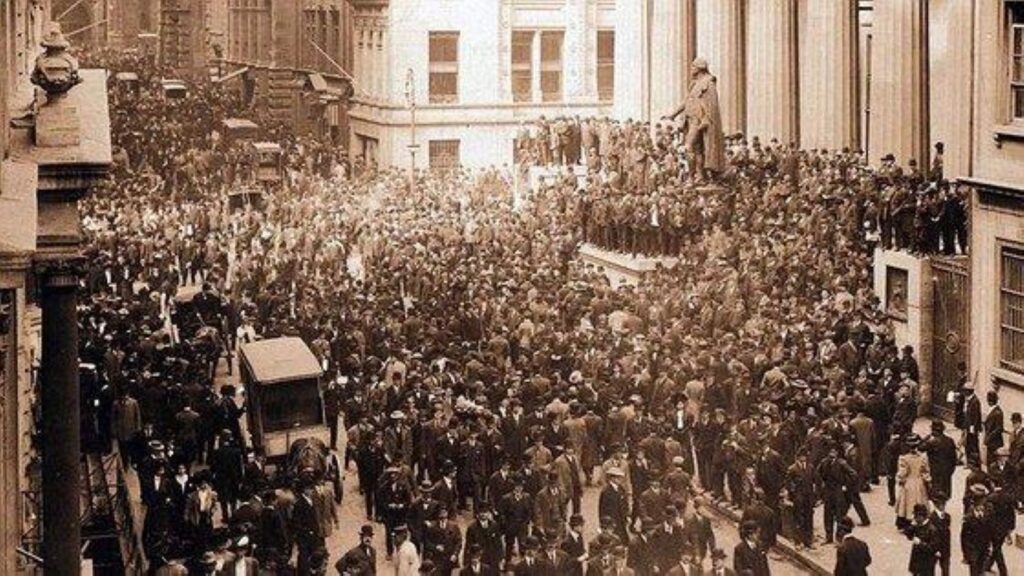

The crisis of 1907 was particularly severe in the United States, with numerous bank failures. The fragmented American banking structure, lacking a central bank, proved unable to provide adequate credit in difficult times. American bankers had to borrow 36 million dollars in gold from London to mitigate the consequences of the crisis, but this dependence on foreign—especially British—capital soon became intolerable. In 1913, the United States finally adopted a central banking system: the Federal Reserve System.

Crisis of 1913 and the wartime cycle of 1908–1921

From 1910 onward, capital investment expanded in industry, and the automobile sector began to gain real importance. In 1909, France produced 45,000 vehicles; by 1913, production had reached 91,000. In Eastern Europe, the metallurgical industry developed quickly: pig iron production rose from 360,000 tons in 1909 to 5 million tons in 1913. Military spending increased and stimulated the steel industry. The German economy was particularly prosperous, and the capital-goods sector had already become important. This sector was temporarily hit by the crisis of 1913, before the First World War gave a new boost to overall economic activity. The United States emerged as the main beneficiary of the war: from being a net debtor, it became the world’s leading creditor. Shielded from the conflict, its economy operated at full capacity to supply the needs of the belligerent nations. Having already caught up with Britain, the United States soon surpassed it to become the leading industrial country of the twentieth century.

The 1920–1929 cycle

The period from 1920 to 1929 may be considered a major Juglar cycle bounded by two crises. The depression was noticeable but relatively brief, while the expansion was much longer and very strong, especially in the United States. The year 1929 stands as a peak in the history of American and global prosperity.

The 1920 reconversion crisis

The American economy benefited greatly from the stimulus that wartime demand provided to its productive apparatus, both in 1914–1919 and again in 1939–1945. While the United States emerged strengthened from the First World War, Europe had to rebuild from destruction. The United States became the world’s leading exporter of goods and services and its main supplier of capital. The years following the end of the war were marked by reconstruction challenges.

In early 1919, the U.S. government created the American Relief Administration to assist populations in Central Europe threatened by famine. By June 1939, U.S. aid delivered through the A.R.A. amounted to 1.214 billion dollars, eventually reaching 1.415 billion. Of this total, 29% was paid in foreign exchange or gold, 63% through credits, and only 8% as donations. However, following the 1929 crisis, many of these credits would never be repaid.

Nevertheless, the situation in Western Europe was less catastrophic and, despite reconstruction needs, the central issue became the transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy. In both the United States and Europe, there were fears of massive unemployment due to demobilization. The decline in government purchases and the increase in labor supply were viewed as sufficient causes to trigger a recession.

These fears did not materialize because the forced savings accumulated during the war helped finance purchases of durable consumer goods needed to replenish household stocks. In response to this real boom in consumer demand—particularly strong in Britain—firms had no difficulty immediately hiring demobilized soldiers. Demand for intermediate goods and capital goods increased through a similar inflationary expansion process.