Speculation disconnected from economic activity—that is, from production levels and profits—contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Experience in this field is consistent. But one must then ask about the causes of such speculation. Why was it so long and so “crazy”? Certain authors consider that the speculation of 1927–1929 was the result of monetary inflation brought about by a cheap-money policy and the ease of credit in the Federal Reserve System.

The Federal Reserve, responding favorably to this request, lowered its discount rate and, through open-market operations, purchased large volumes of government securities in order to push interest rates downward (the rise in prices caused by increased demand reduces the yield or real interest rate of fixed-income securities). “In 1927, during the second half of the year, together with major acceptance operations, it was the most considerable and most daring move the Federal Reserve System had ever undertaken, and in my view, it resulted in one of the most costly errors made by any banking organization in the last seventy-five years.” Lord Robbins, who quotes this passage and strongly criticizes U.S. monetary policy along the same lines as A. C. Miller, concludes: “This policy was crowned with success. The threatening recession was prevented. London’s situation improved. Production and the stock market entered into a new pact with life. But everything suggests that from that moment on the situation escaped all control.”

In 1928, American authorities were absolutely frightened. But the forces they had unleashed had gained too much momentum for them to restrain. Confidential warnings were issued in vain; discount rates were raised in vain. The speed of money circulation, the delirious expectations of speculators and company promoters swept everything along. “The most reasonable men in the nation awaited with resignation the inevitable disaster.” It was, in the last analysis, the deliberate cooperation between central bank leaders and the deliberate “reflection” of Federal Reserve authorities that created the most harmful phase of this prodigious transformation. This is the monetarist explanation of the October 1929 crisis, an explanation that J. K. Galbraith rejects with irony, claiming that it is nothing more than “a tribute paid to a recurring preference, in economic matters, for a formidable absurdity.” Galbraith is too harsh, and a more nuanced critique is required. Lord Robbins’s error is not in emphasizing the obvious inflationary consequences of an agile monetary policy, but in making this policy the sole cause of the disaster. Just as there is no monistic explanation of the Great Depression, neither is there a monistic explanation of the crash, although the causes of the latter are probably fewer than those of the recession that occurred between 1929 and 1932. Let us admit, then, that monetary policy facilitated or even primed speculation; but it is not certain that, in the absence of other factors, such speculation would have been so intense. As is well known since Keynes, offering abundant and cheap credit is not enough to guarantee that borrowers will automatically appear. The other causes (and the list is surely not exhaustive) of the speculative movement stem from structural and psychosocial factors.

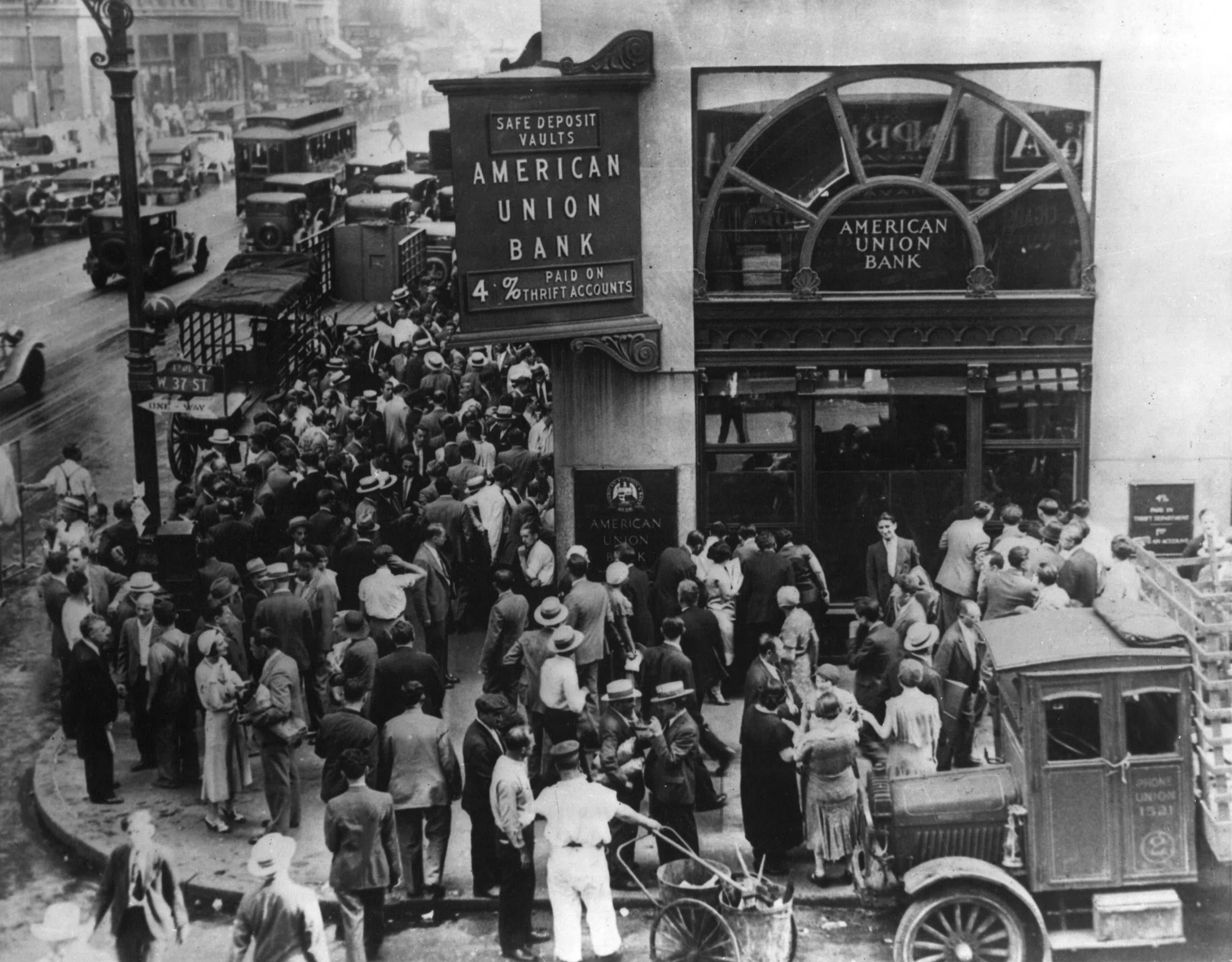

The extraordinarily fragmented American banking structure has, since the early nineteenth century, been a weak point in the U.S. economy. We will have occasion to note in the monetary history section that the organization of the American money market was highly favorable to financing speculation, which could feed on very short-term loans. Interest rates depended on stock-market speculation, and for this reason, during a boom, they could rise to 12 or 15 percent without reducing demand. Rising prices and rising interest rates could thus be linked in a cumulative and explosive mechanism.

The expansion of investment trusts and holding companies pushed stock prices upward. Furthermore, large-scale agreements were carried out along these lines. Galbraith cites several big names, their statements, and their maneuvers during the speculative boom. Many of the best-known businessmen lent their authority to encourage the upward speculation. Lord Robbins, writing without the benefit of hindsight, is more discreet than Galbraith regarding names, but more precise about the behavior of major speculators, who profited at the expense of a public that had become the easiest to deceive. “Such an imposing structure of high-finance transactions contributed to creating a mindset that ignored the possibility of fraud or serious error.” One must therefore turn, ultimately, to the psychosociological factors that characterized the behavior of the American public, which, having access to credit and encouraged by the staged enthusiasm of major capitalists, fueled the rise.