From the industrial revolution to the second world war

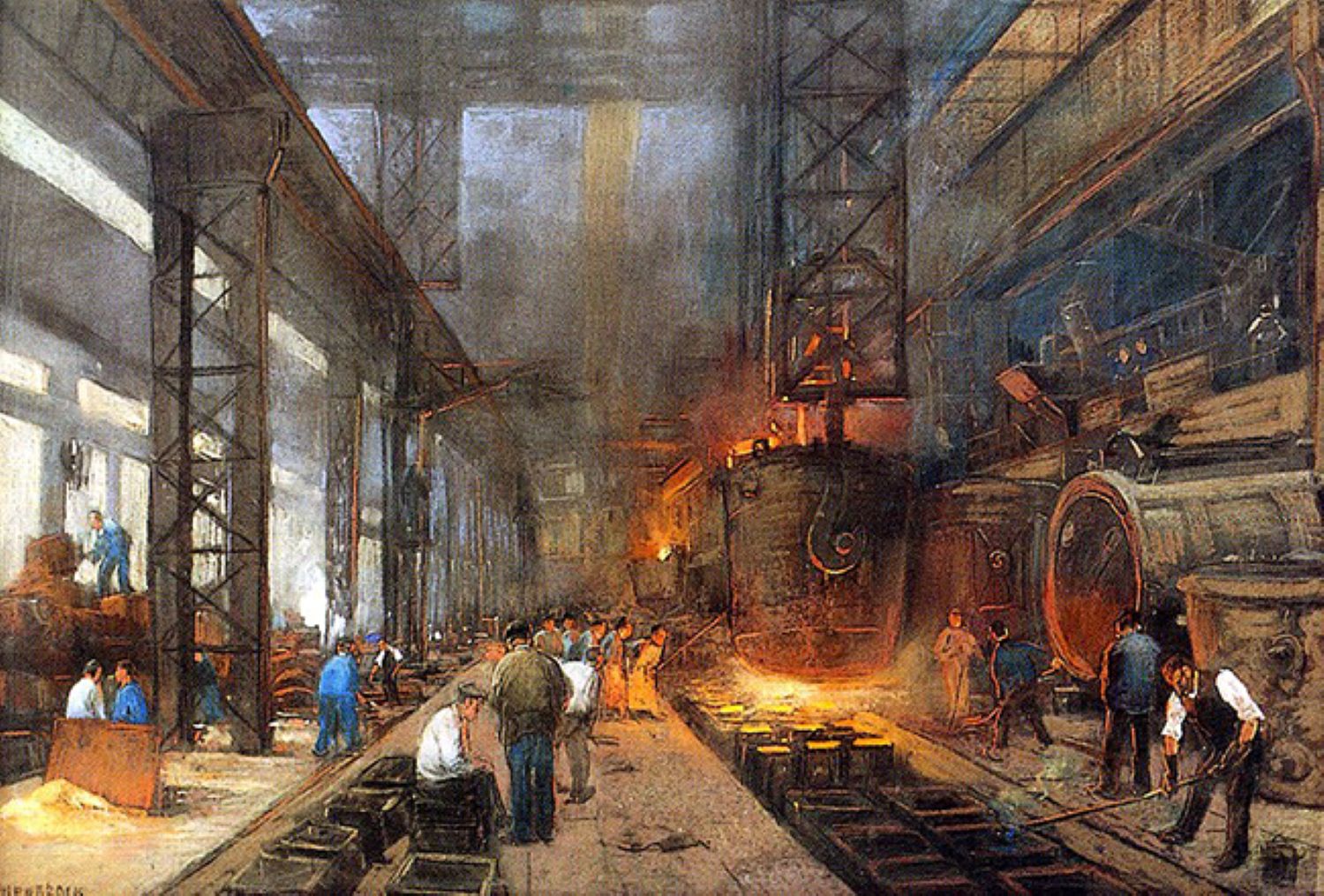

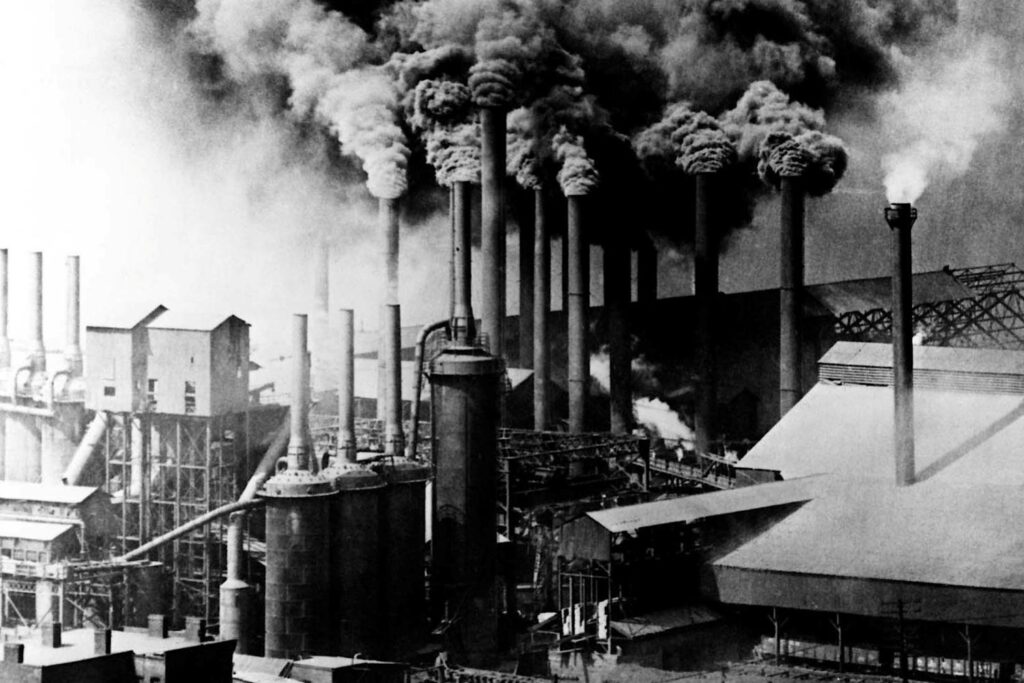

The implementation of industrialization is a complex mechanism whose causes are not always easily identifiable. Contemporary capitalism was born with industrial society after a revolution in production techniques that made it possible to accumulate an ever-increasing volume of capital.

We will attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of this process of industrialization, describing the experience of a certain number of countries: England, France, the United States, Germany, Russia, and Japan. While there are common features in the development history of all these countries, it is essential to point out the differences that arise from the various periods, the behavior of different economic agents, inequalities in resources, and political and social institutions. The British model of the “industrial revolution” is the one most often evoked. It suggests liberal capitalism and the predominance of private initiative. This model is the source from which Rostow derived the elements of his “take-off” theory and Schumpeter the foundations of his theory of innovation and development. In reality, the historical experiences we will describe do not share the same characteristics. For development to emerge, a certain number of “prerequisites” are indispensable in agriculture, transportation, demographics, the capacity for invention, and innovation. The latter point is particularly important, as the various experiences could be classified according to each country’s relative ability to generate an entrepreneurial “class.”

In the Anglo-American experience, private initiative played a decisive role. The English aristocracy knew how to invest its savings first in agriculture and later in industry. Merchants managed to transform themselves into industrialists as soon as inventors provided them with new means of production. In a later period and in a different environment, Americans demonstrated the same spirit of adaptation to structural evolution.

In France and Germany, private and public initiatives played complementary roles. The spirit of innovation was not the monopoly of private entrepreneurs.

Russia and Japan offer two contrasting examples: in Russia, the inability of the ruling class to innovate—meaning to provide business leaders—led the state to take all initiatives and turn to foreign capital and entrepreneurs, who were the founders of Russian industry. In Japan, the state played no less an essential role in launching industrial development, but the Japanese ruling class was able to adapt to the demands of an industrial economy. Capital and techniques were imported from abroad, but without ever replacing national initiative. Mental structures played an essential role in the industrialization process of all countries.

Title I, devoted to the study of the industrial revolution in some capitalist countries, will allow us to highlight these various aspects of the entrepreneurial function in the advent of industrial society. We will then study the social consequences of the 19th-century industrial revolution.

Title II will address the historical problem of fluctuations and economic crises that profoundly marked the development of capitalism until the Second World War, whose high point was the crisis of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Title III, dedicated to monetary history, will emphasize the fundamental role of key currencies in international monetary relations. The gold standard of the 19th century was, in reality, a sterling standard, and the gold exchange standard has been based, since 1922, on the international role of the dollar and the pound. Alongside the problems of reconstruction, we will again face the contemporary aspects of these mechanisms in the second part of the work.