Despite the uncertainty inherent in growth statistics, it is beyond doubt that between 1815 and 1914 both total and per capita real income grew more slowly in France than in other industrial countries (England, the United States, Germany, Belgium). The next section will show the scale and pace of this growth. For now, we shall review the factors that may explain the delay of the French economy, though it is not always easy to determine their relative weight. These unfavorable factors relate to economic and social structures, the mechanisms of economic activity, and protectionism.

a) Demographic trends

As seen in the first section, France was the only industrial country of the nineteenth century whose population grew at such a slow pace. This demographic stagnation, accompanied by aging, could only have had a negative influence on final demand: “In general there is a positive relationship between population growth rates and product growth. All correlation coefficients are positive and high, and verification indicates that most of them are significant at the 1% level.” Moreover, J. J. Spengler, in the Rapports du Ve Congrès international des Sciences, wrote: “When the population grows rapidly, entrepreneurs and the economic community tend to be animated by an expansionist and aggressive spirit. Everyone sees their markets expand and expects that increases in sales opportunities will absorb momentary overproduction and an apparently excessive production capacity… When the population does not grow or declines, less optimistic expectations may prevail, though this result is not automatic. It is also likely that a slowdown in population growth contributes to rigidifying the economic structure of a society.”

France experienced such structural rigidity as labor mobility remained very limited throughout the nineteenth century. Internal migration from the primary to the secondary and tertiary sectors was relatively less significant than in other industrializing countries. Small-scale rural property kept peasants tied to the land; at the same time, while France exported its engineers and specialists, it imported less skilled labor from Spain, Germany, and Central Europe. The absence of demographic pressure slowed both aggregate demand and the labor supply.

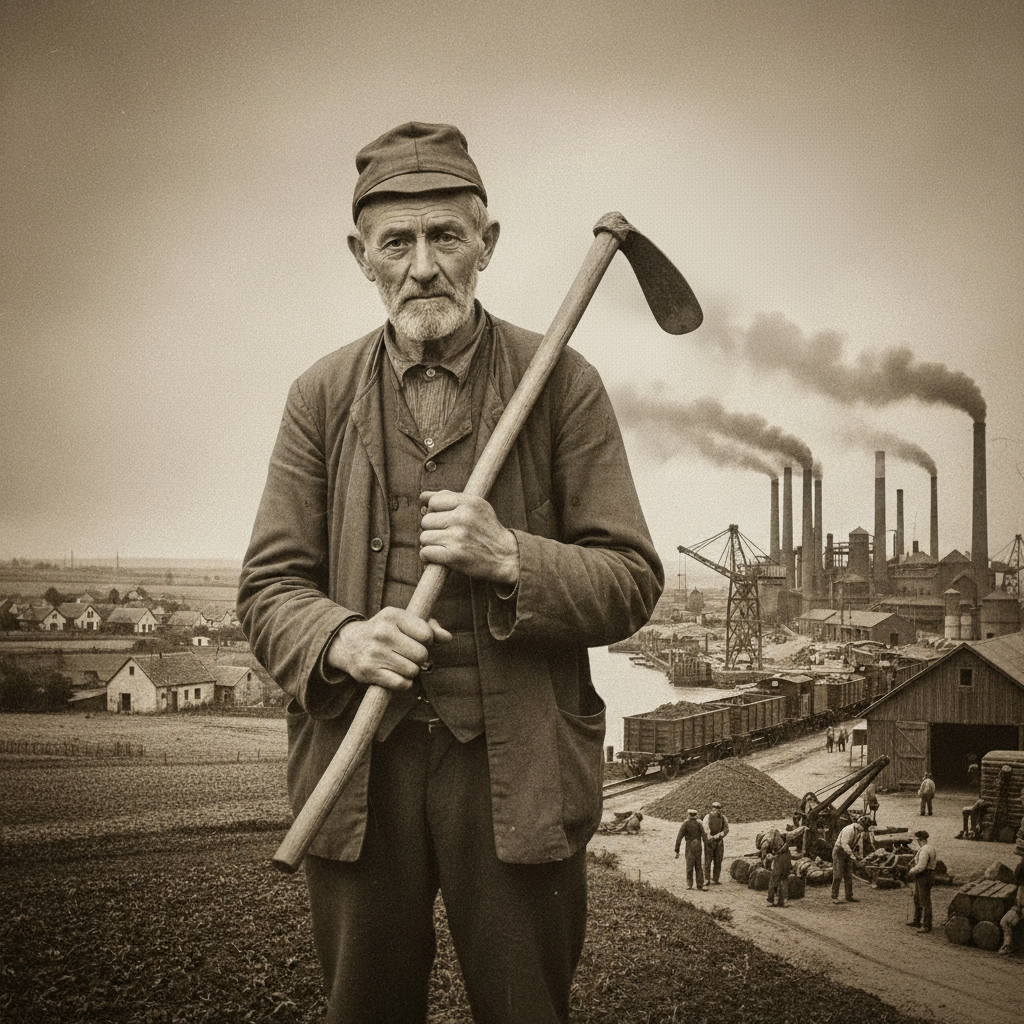

b) The insufficiency of natural resources

We have already noted the limited importance of coal and iron ore resources. In 1890, 53.5% of French imports were raw materials necessary for industry, compared to 36.8% for the United Kingdom, 42.6% for Germany, and 36.4% for the United States. By the end of the nineteenth century, France was the only industrial country that had to import coal for domestic needs, while the others had exportable resources. Coal prices were much higher in France than in other industrial nations: according to calculations by the Comité des Forges, coal should have cost 11.07 francs per ton between 1885 and 1890, compared with 6.96 in England, 9.37 in Belgium, and 6.59 in the United States. This was a significant disadvantage in an era when coal was the primary source of energy.

France discovered its iron ore wealth very late and suffered a heavy blow, as noted earlier, with the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine in 1871. The Briey basin was discovered in 1894. By 1910, 90% of iron production came from Lorraine, with 75% from Briey alone.

c) Savings and investment

Nineteenth-century France was not short of capital, but its savings were not sufficiently productive. There was hoarding, and savings were poorly directed. According to R. E. Cameron’s estimates, less than half of net savings during the century were invested in agriculture and industry. “Transport and financial institutions absorbed a little over 20 billion francs between 1870 and 1900, leaving only 50 to 60 billion for agriculture and industry, an annual average of 600 million. This is the crux of the matter. The growth of French industry did not keep up with that of neighboring countries because France did not invest.”

This weakness in investment was partly due to demographic trends and, to a lesser extent, to the lack of coal and iron. Yet the nineteenth century was the age of saving and rentier income. Population aging encouraged saving, but this saving was channeled into foreign investment and loans to the state. Probably more than half of French savings went in these two directions. The state could have used this saving for productive purposes, but it usually served to finance budget deficits.

French investors generally preferred security to the prospect of high profits. Alfred Sauvy drew the conclusion: “If France has been granted the reputation of banker of the world, it is because, lacking internal development, its capital sought employment abroad… From 1880 to 1913, the French portfolio increased its holdings in foreign government securities by 42 billion… It was a long martyrdom… Borrowing countries paid interest with new loans. Certainly, they had not invented this procedure. After 1914, when France was unable to continue this financial juggling, the circuit collapsed. The more scrupulous countries repaid loans in paper francs, with an almost total loss. The rest simply stopped paying… The French could not invest in real wealth; they had lost the pioneering spirit, lacked confidence in the future, and, eager for security, could not act differently. Their behavior was logical, coherent; by refusing to have children, they had lost the creative spirit. They sought 3% from national debt squandered in deficit budgets or 4% from foreign bonds. And so, by not wanting to raise children, the French helped others raise theirs.”

d) Protectionism

France has always been “protectionist” and “Colbertist.” The state defended national hegemony by controlling and protecting it from foreign competition. In the long run, this policy could only hinder the spread of new techniques and growth. Agricultural protection helped maintain high prices, while tariffs on coal and raw materials increased production costs. The prohibitive duties on coal and metallurgical products imposed by the Restoration in 1816 slowed the development of coke-based iron production. Mechanical industries and other sectors consuming coal, iron, and steel would have preferred to buy their raw materials at world prices. They would then have had lower costs and thus could have produced at more competitive prices in world markets.

It should also be recalled that France suffered more political upheavals during the nineteenth century than most industrial countries. There were revolutions and wars: revolutions in 1830 and 1848, the Crimean War (1854–1856), and the war of 1870. These upheavals cost dearly in men and resources and only further delayed economic progress.

These were the essential causes of the delay in French growth during the nineteenth century. In the next section, we will detail the pace of this growth, but before that it is worth recalling Richard Cobden’s opinion on the place occupied by the French economy in international competition. Commenting on the results of the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851, Cobden noted: “England has no rival in the production of manufactured goods… but there is one country that, in general opinion, occupies first place in the manufacture of items that require delicate handling, impeccable taste, and the most skillful application of the laws of chemistry and the art of manufacturing; that country is France… As merchants, the English are far superior to the French. But as manufacturers, the French stand entirely on our level. If the French had the natural advantages we possess, they would have done and would do everything we have done.”