During the years 1922–1929, a true construction boom took place, covering both housing and factories. During this period, two new industries expanded rapidly: the automobile industry and the electricity industry. Both generated important induced effects.

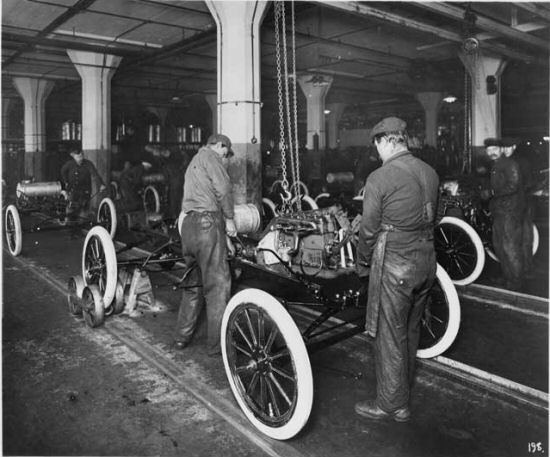

Automobile production increased by 33% per year between 1923 and 1929. As a consequence, the production of oil, steel, rubber, and road construction also rose. The generation of electric power doubled between 1923 and 1929, and the output of all electrical appliances followed the same upward trend. Investment opportunities were therefore numerous, and annual investment expenditures represented more than 20% of the gross national product. Except in 1924, when unemployment reached 4.5% of the active population, joblessness was about 2%, a relatively low level. From 1922 to 1929, total production of manufactured goods increased by nearly 50%. American prosperity spread to the rest of the world through imports and foreign loans. Figure 18 shows that world exports followed industrial production in its upward movement, even surpassing it between 1925 and 1926.

Runaway inflations in eastern europe and germany

It was mainly in eastern Europe where the economic disruptions were most severe after the dismantling of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary emerged from this redrawing of the European map. A wide free-trade area had just broken apart, to the detriment of exchanges among these new countries, all of which were devastated. Rising nationalisms did the rest by enclosing each country behind tariff barriers and attempting to create and develop new industries. Czechoslovakia retained a large part of former Austrian industries, but did not have a sufficiently large population to absorb their output. Instead of continuing the traditional exchange, this country built new spinning mills, depriving Austrian yarn of its natural outlet. The economies of central and southeastern Europe might have developed if external trade had been facilitated.

German hyperinflation unfolded in two stages: first, the rise in the exchange rate of foreign currencies (fall of the mark) was faster than the rise in domestic prices; then prices began to rise faster, but foreign currencies (pound, dollar, franc) had already begun to replace the mark as a means of domestic payment. During this period, and until early 1923, German production increased. From March 1923 onwards, the German government implemented a stabilization policy that eventually succeeded under the leadership of Dr. Schacht. The rentenmark, backed by national wealth, endowed with legal tender, and equal in value to the prewar gold mark, restored confidence in the German currency. The German government received an international loan in 1924, marking the start of a flow of foreign capital into Germany. This loan was linked to the difficult issue of war reparations.

The Reparations Commission created by the Treaty of Versailles had estimated at 6.6 billion pounds sterling the total war damages that Germany had to pay to the devastated countries. The French government counted on these reparations to rebuild ruined regions and balance its budget. A commission chaired by the American Dawes estimated that Germany should pay between 50 and 150 million pounds sterling annually for an indefinite period. The first payment was to be facilitated through an international loan of 40 million pounds (the Dawes loan).

The reparations issue gave rise to constant friction between France and its Anglo-American allies. French politicians likely did not grasp the economic implications of the transfers being demanded, and focused primarily on the monetary dimension of the problem. The British and the Americans, whose countries had not been devastated, could afford to remain calm and focus on the investment opportunities for their capital. However, their strategy failed because a large part of the capital invested in Germany was lost in the German bankruptcies of 1929–1932.

Economic fluctuations in the interwar period and the world crisis

While the nineteenth century witnessed the birth and development of industrial civilization within the capitalist system, the period 1919–1939 was marked by the most severe crisis ever experienced by that system. After a reconversion crisis followed by a brief depression in 1920, the major industrial countries benefited from a phase of expansion that reached its peak in 1929. Yet the extent of prosperity varied widely across countries, and Britain did not share in it after the deflationary experience of 1925 that accompanied the return to the gold standard.

The crisis broke out in October 1929 with the crash of the New York Stock Exchange. The depression that spread rapidly from the United States to the rest of the world was the deepest ever recorded. This shock appeared all the more serious for the future of capitalism because it occurred at a time when the collectivist system was being established and developed in the U.S.S.R.