Devaluation not only failed to prevent capital flight; it frequently intensified it. Most Latin American republics, whose currencies depreciated in 1929 and 1930, resorted to exchange controls in 1931 and 1932. In Europe, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, and Portugal combined devaluation with exchange controls. In 1936 Germany and Poland adopted exchange controls while avoiding devaluation. Nevertheless, Nazi Germany introduced procedures such as parity subsidies. In this way Germany maintained a bilateral currency system with Central European countries that had been particularly sensitive between 1929 and 1935. France, which had remained faithful to the gold parity of existing contracts, nevertheless imposed import quotas to reduce its external imbalance. Its foreign trade contracted on a scale comparable to Germany’s and far more sharply than that of the world as a whole.

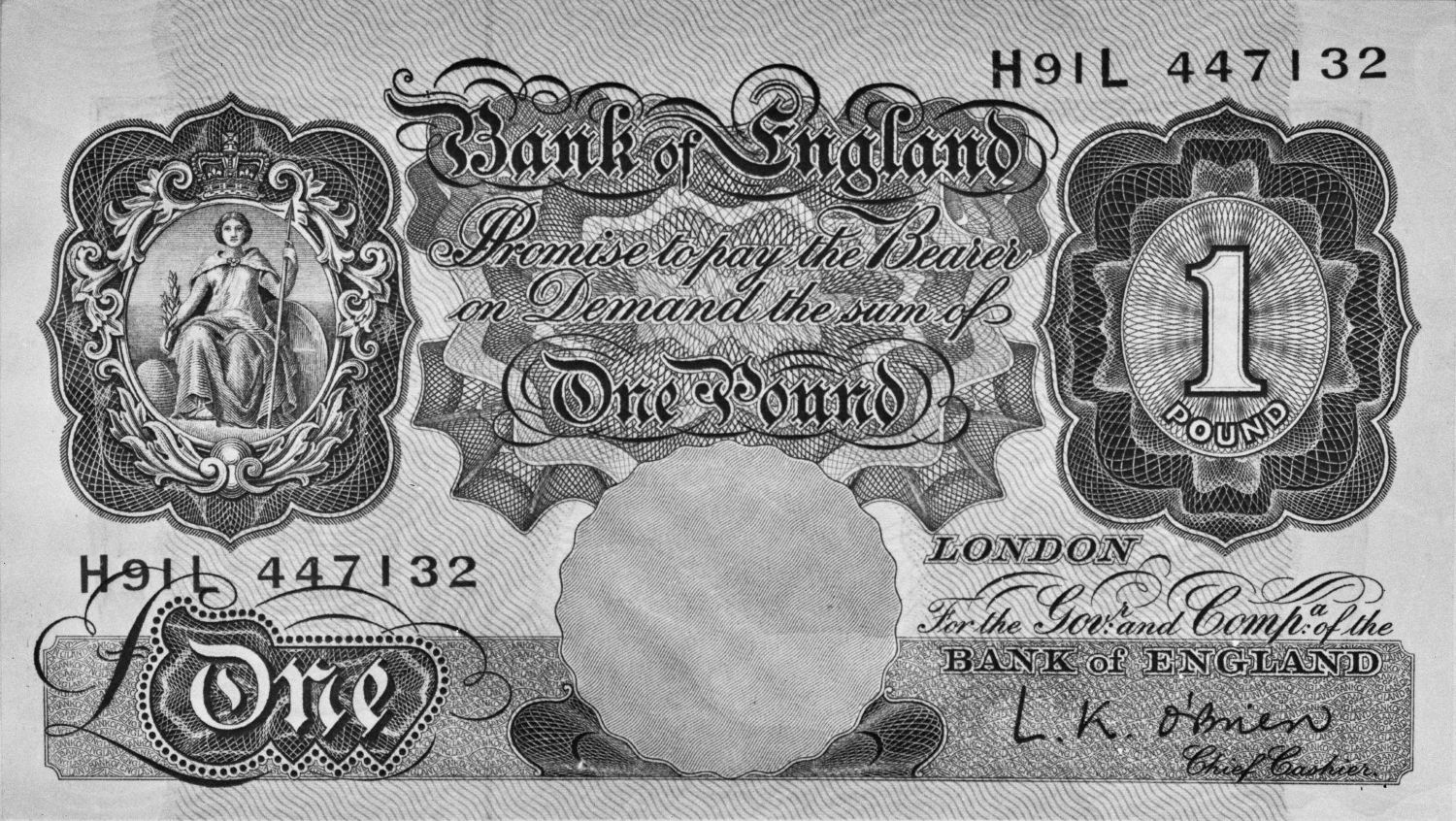

With the outbreak of the Second World War, exchange controls became widespread as governments faced the need to mobilize all resources in foreign means of payment. Protectionism and economic dirigisme expanded, as governments had little room for choice; direct control over resource allocation became essential to sustain the war economy. Capital movements were consequently blocked. A notable exception was the sterling area. On 3 September 1939, the British government introduced exchange controls but allowed full freedom of payments and capital movements between the United Kingdom and other members of the sterling area. These countries adopted the same principle in organizing their own controls. The sterling area thus preserved a system of multilateral trade and payments in a world increasingly constrained by rigid bilateral agreements, at least until 1948. Within this area, sterling remained freely transferable and continued to function, though on a reduced scale, as an international currency. From the beginning of the war, the sterling area contracted largely to the dimensions of the Commonwealth. A decree of 10 July 1940 listed its members for the first time: the United Kingdom and its Dominions (except Canada and Newfoundland), the colonies and territories under Egyptian mandate and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, as well as Iraq and Iceland, which were not part of the Commonwealth. No formal institutional authority was created; the sterling area operated largely on the basis of informal understandings. The international role of sterling was at once diminished and preserved.

Reconstruction and development of the capitalist countries since the Second World War

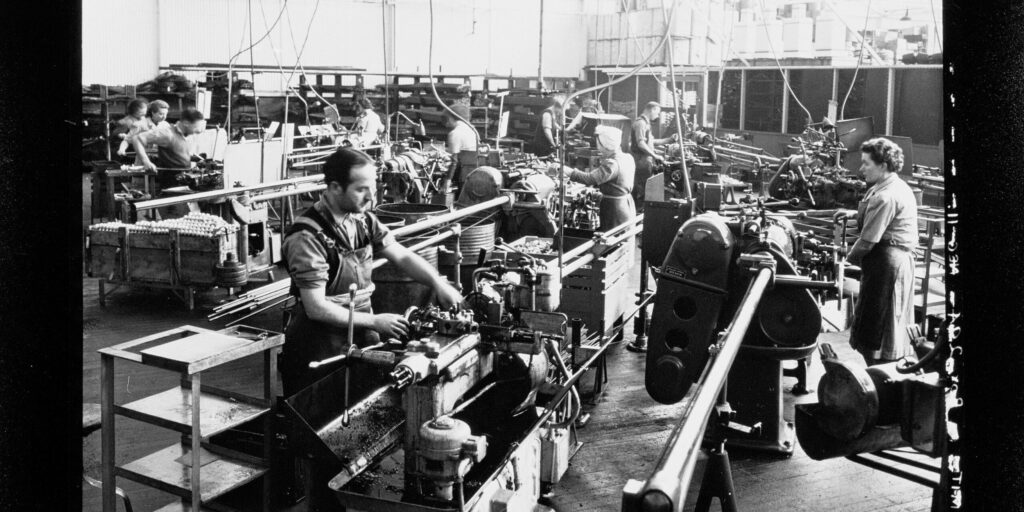

The Second World War marked a decisive turning point in modern history, inaugurating a phase of renewal and rapid transformation. Whereas the interwar years had been overshadowed by depression and social distress, the postwar period was characterized by economic progress and sustained growth in the industrial countries. During the interwar years, some economists believed that investment opportunities were disappearing and that an era of maturity and stagnation was imminent. The capitalist mechanism appeared rigid, while fascist regimes found fertile ground in Germany and Italy. The international monetary system had collapsed in 1930; protectionism had spread, and international cooperation had failed. At the same time, collectivism demonstrated its capacity for survival and development in the Soviet Union, challenging capitalism’s monopoly as an economic system.

After the Second World War, a vast new industrial revolution transformed inherited structures and opened expansive prospects for economic development. The discovery and exploitation of atomic energy, advances in electronics and chemistry, the conquest of space, and demographic expansion created new opportunities for both public and private investment. If the central problem of the interwar period had been depression and unemployment, the defining issue of the postwar era became inflation, the characteristic ailment of rapidly expanding economies.